Image of small fire traveling across the forest floor provided by Emma Renly via Unsplash.

TL;DR: Wildfires are worsening due to climate change and human activity, with about 84% of fires caused by people. While fire suppression is necessary for immediate safety, a century of aggressive suppression has disrupted natural fire cycles, making forests more vulnerable and increasing firefighting costs. Controlled burns, which are carefully planned low-intensity fires, can reduce hazardous fuel buildup, promote healthy ecosystems, and support biodiversity. Versions of controlled burning have been used for millennia and are gaining renewed attention as affordable and effective prevention strategies. A balanced approach that includes suppression, prevention, and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions can help lower wildfire risks and build long-term resilience.

Wildfires are becoming a growing concern across the United States and many parts of the world. Climate change is contributing to hotter, drier conditions, which in turn lead to more severe and damaging wildfire outbreaks. Human activities also play a major role, with about 84% of wildfires caused by people.

The way that we suppress wildfires today heavily influences the nature of wildfires to come, making it necessary to practice balanced fire suppression and prevention strategies.

Fire suppression

Fire suppression, also known as firefighting, refers to the actions taken to mitigate or extinguish a fire that has already started. It is responsive and necessary to protect humans and sometimes wildlife from the dangers of an inferno.

Fire consists of oxygen, heat, and fuel. Removing any one of these three things will extinguish a fire. Fire suppression techniques include forming a firebreak line, applying water or a foam mixture, and starting another fire to consume the fuel and oxygen in the path of an advancing wildfire. Firefighting resembles a military command system, which allows firefighters to respond efficiently and collectively.

After a wildfire has ended, the process of “mopping up” ensues. After a fire is contained, the area must be scanned for any remaining burns to be extinguished. When ground conditions are dry, heat can travel beneath the forest surface and continue to burn for days or even months. Mopping up prevents these burns from regenerating to the surface.

Fire suppression costs

Fire suppression can be costly. Over the last five years, the United States’ Forest Service and DOI agencies spent a total of $2,989,051,200 on average each year in fire suppression costs. Over the last few decades, fire suppression costs have more than tripled due to climate change, wildland urban interface (WUI) growth, insect infestations, and invasive species.

Fire suppression history and consequences

One reason why fire suppression is so expensive today is due to the effects of past fire suppression. For nearly a century, beginning in the 1800s and continuing well into the 1900s, the United States practiced a policy of total fire suppression. An event called the “Big Blowup” in 1910, which referred to a series of forest fires that burned three million acres in Idaho, Montana, and Washington, cemented the idea that total fire suppression was the only way to protect national forests.

The Forest Service’s Smokey the Bear character, the Weeks Act of 1911, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the 10 a.m. policy (which aimed to suppress every fire by 10 a.m. the day after it was reported) all helped promote total fire suppression. New infrastructure and technologies, such as road networks, airplanes, and certain fire suppression chemicals, made these efforts more effective.

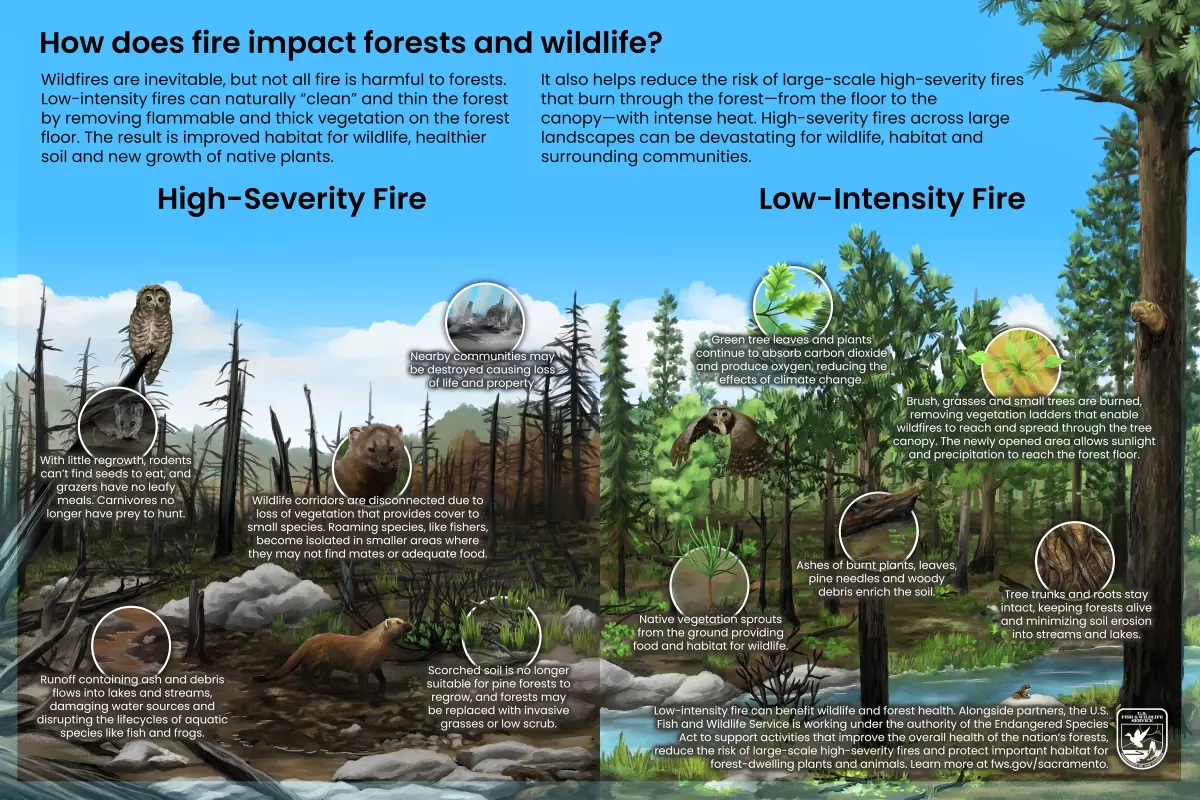

The policy of total fire suppression was well-intentioned, but based on a limited understanding of the ecological role of fire. It wasn’t until the 1960s that scientists began demonstrating the positive role that fire could have on forest ecology. By constantly suppressing fire, we have minimized the amount of forest burned, but we’ve also amassed dead biomass in fire-prone ecosystems. This means that when fires do break out, they are likely to become more severe and harmful.

Total fire suppression puts stress on trees due to overcrowding and causes fire-dependent species to become endangered. These policies have allowed young conifer trees to become fuel ladders, transferring fires near the ground to the tree tops, where they can cause more damage and have also led to invasive forest species invading grasslands, harming the habitats of large mammals.

Controlled burns and fire prevention

Controlled burns, also referred to as prescribed fires, can help solve some of the problems of fire suppression. These burns have various benefits:

- They remove invasive species

- They provide more forage for game animals

- They promote plant growth

- They improve habitats for threatened species

- They minimize the spread of pest insects and harmful diseases

- They recycle nutrients back into the soil

There are various types of prescribed burns for different needs and situations, such as broadcast burning, pile burning, and Indigenous cultural burning. Sometimes controlled burns are used on private property, as well as national land.

Prescribed burns include intensive planning and equipment. Often, the fire is contained by cutting a line around its perimeter, clearing away forest debris on the ground to stop the flames from escaping its prescribed bounds. Although all fire comes with some risk, with proper planning, 99.84% of prescribed burns go according to plan.

Controlled burns play a vital role in helping prevent extreme wildfires by removing the thick and flammable vegetation from the forest floor. Ecological forest management strategies, like prescribed burns, are far less expensive than firefighting costs. It is better to be preventive than reactive. Organizations such as Blue Forest help build partnerships and find the funds needed to put controlled burns and other forest resilience strategies into practice.

Indigenous cultural burning

Before widespread fire suppression in the United States, many Native American tribes practiced Indigenous cultural burning for millennia. This practice served various purposes, such as clearing land for crops, travel, and campsites, fostering specific flora and fauna, and aiding in hunting. Indigenous cultural burning also protected against severe wildfire outbreaks and promoted ecological diversity.

This practice shaped many iconic American landscapes into what they are today. It promoted Oak and chestnut trees in the East, and tall grass prairies in the Midwest. In California, Native American fire stewardship created and fostered gardens in nature, improving soil quality, cultivating certain plants, and creating a more resilient landscape. Muir Woods and Yosemite Valley both saw this kind of Indigenous stewardship.

Cultural burning largely disappeared during the twentieth century, although there is a rising movement today centered on handing land stewardship back to Native tribes.

The recent history of controlled burns

In the 1970s, the era of total fire suppression began to lift. Based on new research, the Forest Service implemented a “let-burn” policy, allowing certain naturally caused fires to burn in designated wilderness areas. However, even this cautious approach faced pushback.

Today, the U.S. government permits the use of prescribed fires in certain areas. Between 2011 and 2019, their use in forests and rangeland areas around the country increased by 28%. In 2019 alone, over 10 million acres were intentionally burned. Most prescribed fires take place in the Southern United States, but in recent years, they have also been implemented in Western states such as California.

The growth of wildland-urban interface (WUI) areas can complicate controlled burns. WUI areas are regions where human settlements meet wildlife. Controlled burns can temporarily affect air quality near these communities and must be carefully considered when planning a prescribed fire.

Balancing different strategies: Building a more resilient future

Fire suppression strategies protect people, property, and ecosystems against high-intensity wildfires. However, proactive fire prevention methods, such as controlled burns, can reduce firefighting costs and support more fire-resilient landscapes. Both techniques are vital.

Balancing these approaches while addressing carbon emissions and global warming will help combat severe wildfires and provide a safer future for all.

If you’re interested in measuring air quality levels related to controlled burns or other wildfire activity, you can contact Clarity for an air quality monitoring quote today. During the 2025 wildfire season in North America, we are offering limited-time discounts on wildfire-oriented air pollution monitoring equipment.